The nonsensical tie-in has long been one of my favorite PR genres, and the coronavirus crisis has created a whole host of examples; Casey Newton posted a particularly egregious one:

Using a current news event as cover is hardly limited to bad PR pitches;1 look no further than this announcement from Google, which used the coronavirus crisis to frame a major change in Google Shopping:

The retail sector has faced many threats over the years, which have only intensified during the coronavirus pandemic. With physical stores shuttered, digital commerce has become a lifeline for retailers. And as consumers increasingly shop online, they’re searching not just for essentials but also things like toys, apparel, and home goods. While this presents an opportunity for struggling businesses to reconnect with consumers, many cannot afford to do so at scale.

In light of these challenges, we’re advancing our plans to make it free for merchants to sell on Google. Beginning next week, search results on the Google Shopping tab will consist primarily of free listings, helping merchants better connect with consumers, regardless of whether they advertise on Google. With hundreds of millions of shopping searches on Google each day, we know that many retailers have the items people need in stock and ready to ship, but are less discoverable online.

For retailers, this change means free exposure to millions of people who come to Google every day for their shopping needs. For shoppers, it means more products from more stores, discoverable through the Google Shopping tab. For advertisers, this means paid campaigns can now be augmented with free listings. If you’re an existing user of Merchant Center and Shopping ads, you don’t have to do anything to take advantage of the free listings, and for new users of Merchant Center, we’ll continue working to streamline the onboarding process over the coming weeks and months.

This has nothing to do with the coronavirus: what this change really means is the biggest missing piece in the Anti-Amazon Alliance is now all-in.

Swiffer and Shelf Space

The concept of a Purchase Funnel was first published in 1925 in Edward Strong’s The Psychology of Selling and Advertising; Strong credited E. St. Elmo Lewis for originally formulating the idea:

Many changes in selling procedure have of necessity been made in the past fifteen years. Among them is the growing recognition of the buyer’s point of view. The development of the famous slogan — “attention, interest, desire, action, satisfaction” — illustrates this. In 1898 E. St. Elmo Lewis used the slogan, “Attract attention, maintain interest, create desire,” in a course he was giving in advertising in Philadelphia. He writes that he obtained the idea from reading the psychology of William James. Later on he added to the formula, “get action.” About 1907, A.F. Sheldon made the further addition of “permanent satisfaction” as essential to the slogan. Very few in 1907 felt the need for the last phrase, but on every hand today is heard the necessity for rendering service, of securing the goodwill of the buyer, of selling him what he needs, of establishing permanent satisfaction…

These changes have taken place so gradually that many salesmen and advertisers have failed to appreciate their inherent relationship to each other or their significance. Many have not seen, that honest service to a buyer in terms of his needs so that he will feel goodwill, and be permanently satisfied, means that the buyer’s interests must be dominant, no the seller’s. And fewer still have see that the easist way, and in fact the only way, to guarantee that this will be achieved is for the seller to present his proposition from the buyer’s point of view.

The AIDA model, as the purchase funnel is also known, is exactly as Lewis described it; I always understood it best in terms of problem-solving:

- Attention: make the buyer aware of a problem they have

- Interest: the buyer becomes interested in solving their problem

- Desire: the buyer becomes interested in your solution to their problem

- Action: the buyer acquires your solution

A classic example of this model compressed into a single commercial is the roll-out campaign for the Swiffer mop:

The entire funnel is in this ad:

- Attention: Traditional cleaning methods stir up dirt

- Interest: Dirt needs to be removed, not just moved

- Desire: Swiffer cloths collect dirt and can be thrown away

- Action: Find Swiffer in the household cleaning aisle

The aisle reference is critical: shelf space was long the linchpin for large consumer packaged goods companies: Swiffer had widespread distribution the moment it launched because P&G could leverage its other popular products when it came to negotiations with retailers. And, of course, simply being on shelves increases the chances customers discover you on their own, or recognize you after repeated exposure in advertising: shelf space provided both distribution and discovery.

Facebook and Discovery

That commerical, I should note, is actually not the best example of how the marketing funnel normally worked for P&G and its ilk; while it included Interest, Desire, and Action, it was mostly about Attention: over the months and years to come P&G would run many more campaigns across media of all types, from TV to coupons to end-caps in retailers, all with the goal of making Swiffer into a habitual purchase. The fact that that commercial compressed all parts of the funnel into 45 seconds was, though, helpful for explaining the AIDA framework!

It was also a sign of things to come: one of the hallmarks of the Internet is that the entire funnel is often compressed into a single Facebook ad that you might only see for a fraction of a second; perhaps something will catch your eye, and you will swipe to see more, and if you are intrigued, you can complete the purchase right then and there. You might even forget about your purchase right up until a mysterious package shows up at your door a few days later.

The reason this works is the sheer scale of Facebook; there are so many people scrolling through so many feeds and swiping through so many stories that the advertising game is basically the inverse of what worked before: instead of carefully planning a multi-pronged advertising campaign to over time move people down a funnel to a purchase decision in front of a stocked shelf, advertisers iterate their targeting criteria and ad content over time to convert customers immediately.

Facebook — experiments with Instagram checkout notwithstanding — is only one piece of the e-commerce stack that makes this possible:

- Facebook helps find the customers

- Shopify or WooCommerce build the storefronts

- Stripe or PayPal handle payments

- Third-party logistics providers package and ship the goods

- USPS, Fedex, and UPS deliver the actual packages

To put it another way, Facebook provides the digital shelves for customers to find what they didn’t know they wanted, and the rest of the ecosystem fills in the pieces.

Amazon the Integrator

When the Internet digitizes what used to be analog assets, we often find out that jobs that were once done together end up in radically different places. The classic example are newspapers: they carried both editorial and advertisements, but it turns out that was simply a function of who owned printing presses and delivery trucks; once the Internet came along advertisers, which cared about reaching customers, not supporting journalists, switched to Facebook and Google, which had aggregated the former and commoditized the latter.

So it is with shelves: when the supply was constrained by physical space, they were extremely valuable for not just discovery but also distribution, but once the Internet made shelf space effectively infinite, it shouldn’t be a surprise that the solutions to discovery and distribution developed differently.

As I just noted, the answer to the former has been Facebook; the answer to the latter, though, is search. I first wrote about this transition six years ago in How Technology is Changing the World (P&G Edition):

That’s great for Amazon, but not so great for P&G: remember, dominating shelf space was a core part of their strategy, and while I’m no mathematician, I’m pretty sure dominating an infinite resource is a losing proposition. What matters now is dominating search. That is the primary way people arrive at product pages like this:

There are two big challenges when it comes to winning search:

- Because search is initiated by the customer, you want that customer to not just recognize your brand (which is all that is necessary in a physical store), but to recall your brand (and enter it in the search box). This is a much stiffer challenge and makes the amount of time and money you need to spend on a brand that much greater.

- If prospective customers do not search for your brand name but instead search for a generic term like “laundry detergent” then you need to be at the top of the search results. And, the best way to be at the top is to be the best-seller. In other words, having lots of products in the same space can work against you because you are diluting your own sales and thus hurting your search results.

The way to deal with both challenges is the same way you break through the noise: you put more focus on fewer brands.

The challenge for P&G and basically everyone else in the retail space is that there is no bigger brand than Amazon itself. According to eMarketer earlier this year, 49% of Internet shoppers start their searches on Amazon, and only 22% on Google; Amazon’s share is far higher for Prime subscribers, which include over half of U.S. households.

This means that Amazon has effectively integrated the entire e-commerce stack when it comes to the distribution of goods consumers are explicitly searching for:

- Customers come to Amazon directly

- Searches on Amazon lead to Amazon product pages or 3rd-party merchant listings that look identical to Amazon product pages

- Amazon handles payments

- Amazon packages and ships the goods

- Amazon increasingly delivers the actual packages

Given this level of integration, it is hardly a surprise that Amazon has for several years been moving into selling its own products as well; not only does it have customers and search, it has data on what people want. Notably, as the Wall Street Journal reported last week, Amazon is allegedly gathering that data from not just its own sales but also those of 3rd-party merchants:

The online retailing giant has long asserted, including to Congress, that when it makes and sells its own products, it doesn’t use information it collects from the site’s individual third-party sellers—data those sellers view as proprietary. Yet interviews with more than 20 former employees of Amazon’s private-label business and documents reviewed by The Wall Street Journal reveal that employees did just that. Such information can help Amazon decide how to price an item, which features to copy or whether to enter a product segment based on its earning potential, according to people familiar with the practice, including a current employee and some former employees who participated in it.

This is, to be clear, a major problem for Amazon, first and foremost because the company has long insisted it does no such thing, and told Congress the same; as John Gruber put it on Daring Fireball, “Amazon isn’t hurting for revenue (especially now), but they are hurting for trust.”

What is truly surprising about this news, though, is that Amazon ever made such a promise in the first place, and, to be honest, that I believed them. On one hand, the reasoning is obvious: making Amazon.com into a platform lets Amazon offer many more items and get paid to do so, as opposed to carrying huge amounts of inventory on which it must expend working capital.

The problem is that the gravitational pull of an integrated offering like Amazon.com is nearly impossible to resist; witness how Windows once spoiled Microsoft services, and Android Google services. Perhaps it was too much to expect Amazon to be any different — or, to put it another way, maybe Amazon always was an integrator, just at a far grander scale.

The Anti-Amazon Alliance

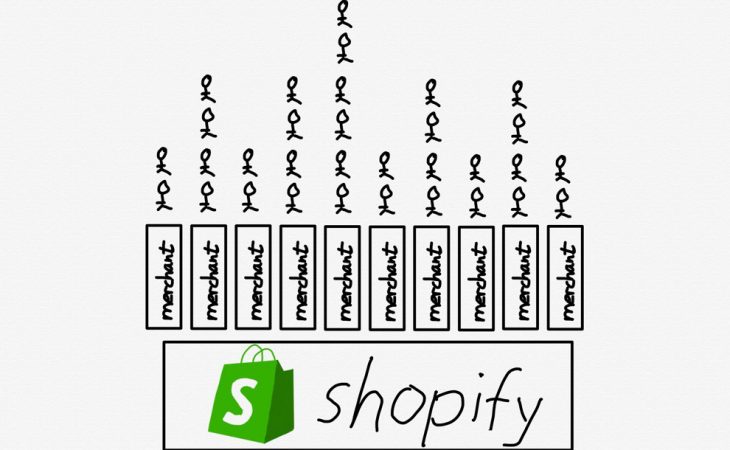

The antidote to an integrator is modularization; that is why I wrote last year that Shopify, not Walmart, was Amazon’s true competitor. From Shopify and the Power of Platforms:

At first glance, Shopify isn’t an Amazon competitor at all: after all, there is nothing to buy on Shopify.com. And yet, there were 218 million people that bought products from Shopify without even knowing the company existed.

The difference is that Shopify is a platform: instead of interfacing with customers directly, 820,000 3rd-party merchants sit on top of Shopify and are responsible for acquiring all of those customers on their own.

This means they have to stand out not in a search result on Amazon.com, or simply offer the lowest price, but rather earn customers’ attention through differentiated product, social media advertising, etc. Many, to be sure, will fail at this: Shopify does not break out merchant churn specifically, but it is almost certainly extremely high. That, though, is the point. Unlike Walmart, currently weighing whether to spend additional billions after the billions it has already spent trying to attack Amazon head-on, with a binary outcome of success or failure, Shopify is massively diversified. That is the beauty of being a platform: you succeed (or fail) in the aggregate.

I sort of skated over that customer acquisition piece, mentioning the sort of discovery that Facebook advertising enables in passing. The big missing piece, though, has been that other shelf functionality — distribution. How do you find the specific thing that you want whereever it might be on the Shopify platform, or WooCommerce or Walmart.com or anywhere else on the Internet?

The answer is not to go to Shopify.com, which, as I noted, no customer knows about; rather the solution is the most powerful search engine on earth — Google. What Google’s announcement unlocks is the same sort of modular stack for distribution that already exists for discovery:

- Google helps find the products on 3rd-party e-commerce sites

- Shopify or WooCommerce build the storefronts (or big box retailers like Walmart)

- Stripe or PayPal handle payments

- Third-party logistics providers package and ship the goods

- USPS, Fedex, and UPS deliver the actual packages

This stack existed before, but inserting an additional payment layer into product discovery made product discovery worse (by limiting the number of products and retailers), hurting the entire ecosystem. Unsurprisingly, Shopify and WooCommerce are partnering with Google to make it easy for small retailers to get into Google’s results, and I wouldn’t be surprised if Google is working with larger retailers as well.

This cooperation is also evidence of Amazon’s growing clout: one of the reasons why Google made Shopping pay-to-play back in 2012 was because the company deemed that the best way to get real-time data for Google Shopping; retailers paying to be featured would be motivated to give Google quality data. Today, though, additional motivation is unnecessary: everyone in commerce is, whether they realize it or not, in the Anti-Amazon Alliance, and that provides plenty of motivation.

The Market Responds

The regulatory angle on this is a surprising one. Start with Google: another reason to go with a pay-to-play model is that it made Google Shopping quite explicitly into something other than a shopping comparison service. That, though, didn’t stop the European Commission from handing down an ill-advised decision that said that Google was guilty of crowding out other shopping comparison services anyways. There is definitely a sense that Google is “damned if they do and damned if they don’t” when it comes to providing anything other than ten blue links.

Moreover, the existence of Amazon and its clear clout in the market rather strongly suggests the European Commission missed the point: market control comes from aggregating customers; Google can’t anymore restrict competition from sites that depend on Google than a car can restrict competition from a trailer it is towing. Winning online is not about functionality, but about what app or website customers open of their own volition. In the case of shopping, that website is increasingly Amazon, and now it is Google that is partnering with others in response.

At the same time, as Benedict Evans detailed last December, Amazon — including 3rd-party merchant sales — accounted for about 6% of U.S. retail sales; to put that in context Walmart accounts for 9%. Yes, e-commerce is growing as a whole even as Amazon increases its share — especially now — but to expect current growth rates to maintain forever is rarely correct, particularly when physical goods (i.e. with marginal costs) are involved.

I would also note that Walmart, like all major retailers, sells private label goods, and unquestionably depends on sales data to decide on what to make, and how much; Amazon should be able to do the same. At the same time, what makes Amazon’s alleged snooping problematic is the fact that it looking at 3rd-party merchants for which it claims it is only an agent, not retailer.

That, though, points to an obvious market-based response: 3rd-party merchants, particularly those with differentiated products and brands, should seek to leave Amazon’s platform sooner-rather-than-later. It is hard to be in the Anti-Amazon Alliance if you are asking Amazon to find you your customers, stock your inventory, package your products, and deliver your goods; there are alternatives and — now that Google is all-in — the only limitation is a merchant’s ability to acquire and keep customers in a world where their products are as easy to buy as bad PR pitches are easy to find.